PROSEARCH UPDATES

December 31, 2024 - Obviousness Rejection Overcome under LKQ Analysis

Obviousness Rejection Overcome under LKQ Analysis - App. No. 29/838,012 - Litter Box – December 31, 2024

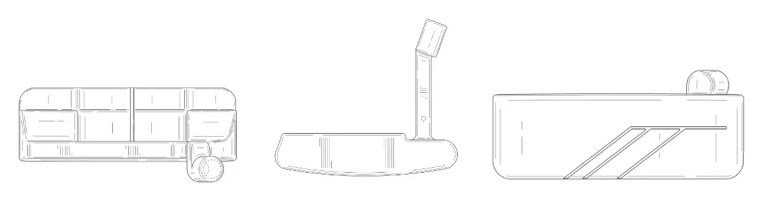

Applicant sought protection for an ornamental design for a litter box, as shown in representative figure 1 above.

The examiner initially rejected the claim under multiple grounds: anticipation under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1), obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103, and drawing inconsistencies under 35 U.S.C. § 112. The anticipation rejection was based on the “Deo Toilet Blue” prior art. The obviousness rejection was based on a combination of the “Tidy Cat Breeze” and “Kobayashi” prior art references, which the examiner argued suggested the same overall appearance as the claimed design.

The applicant requested an examiner interview, where it was clarified that all arguments regarding obviousness needed to be submitted in writing, particularly because according to the examiner, the USPTO “does not have a final position on how we interpret the law on our side, based on the LKQ ruling.”

In the written response, the applicant addressed and resolved the drawing inconsistencies by submitting replacement figures. To refute anticipation, the applicant highlighted material differences between the claimed design and “Deo Toilet Blue.” Applicant focused on the concaved back portion and arcuate side portions of the claimed design, which differed significantly from the straight features in the prior art.

To counter the obviousness rejection, the applicant emphasized two primary points. First, applicant argued that the combined visual appearance of the prior art references differed noticeably from the claimed design. Specifically, the back portion of the “Tidy Cat Breeze” was straight, and while the “Kobayashi” prior art reference had a slightly concaved back, its depth and angle were distinct from the claimed design. The applicant explained that these differences contributed to a unique overall round visual profile for the claimed design, unlike the sharper profile of the references. Second, the applicant argued that no evidence existed to suggest a designer of ordinary skill would be motivated to modify the prior art in the way proposed by the examiner.

The examiner ultimately withdrew all rejections, explaining that with regard to obviousness, the differences in the designs prevented the combined references from achieving the claimed design’s overall appearance. This design patent application highlights how LKQ emphasized the requirement of a record-supported reason for combining references and that the combination of prior art references must achieve the claimed design. The applicant’s success lay not only in identifying specific design differences but also in articulating how those differences impacted the designs as a whole.

December 24, 2024 - Obviousness-type double patenting - Indefiniteness Standard at the USPTO

Obviousness-Type Double Patenting - App. No. 29/866,647 - Golf Club Head - Date: December 24, 2024

The USPTO issued an obviousness-type double patenting (OTDP) rejection for a golf club head design, asserting that the claimed design was not patentably distinct from prior patents D930,096, D967,914, and D979,680. The examiner argued that while the designs differed in specific features such as the striking surface shape, hosel design, and bottom surface patterns, these differences were minor, rendering the designs “substantially the same.” In response, the applicant contended that the examiner failed to justify how an ordinary designer would modify the cited designs to achieve the claimed design, as required by updated standards like LKQ Corp. v. GM Glob. Tech. Operations LLC. The applicant further emphasized that the claimed design’s unique elements, including its larger body, seamless strike face, and distinctive line patterns, made it patentably distinct, especially in the crowded field of golf putter designs where minor variations carry significant weight. The applicant also noted that certain functional aspects of the design underscored its ornamental distinctiveness. Following these arguments, the examiner withdrew the rejection.

The Federal Circuit has made clear that the analysis for an obviousness type double patenting rejection is different from a traditional obviousness analysis in three ways. First, traditional obviousness compares claimed subject matter to the prior art, while non-statutory double patenting compares claims in an earlier patent to claims in a later patent or patent application. Second, double patenting does not require inquiry into a motivation to modify the prior art. Third, double patenting does not require inquiry into objective criteria suggesting non-obviousness. See P&G v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 566 F.3d 989, 999 (Fed. Cir. 2009). While the applicant’s argument about the lack of a modification rationale aligns more closely with statutory obviousness standards, the applicant’s emphasis on the distinct ornamental features of the claimed design effectively addressed the OTDP rejection. The examiner’s decision to withdraw the rejection underscores the significance of demonstrating how even minor differences can establish patentable distinction, particularly in crowded fields like golf putter design.

Indefiniteness Standard at the USPTO – App. No. 29/871,033 – Insulation Resistance Tester – December 24, 2024

The indefiniteness standard at the USPTO, as applied in the case of App. No. 29/871,033 (Insulation Resistance Tester), illustrates how design claims are scrutinized during prosecution to ensure clarity. In this case, the examiner rejected the design claim under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) and (b), arguing that the claim was not described in full, clear, concise, and exact terms, and failed to distinctly claim the invention. The rejection focused on ambiguities in the spatial and geometric relationships of certain squared surfaces in the drawings, which the examiner found unclear to a person skilled in the art. To address these issues, the applicant modified the drawings by converting the ambiguous areas into broken lines, leading the examiner to withdraw the rejection.

The standard for indefiniteness during prosecution is guided by the decisions in Ex Parte Miyazaki and In re Packard. In Miyazaki, the USPTO applied the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard, holding that claims are indefinite if they are amenable to two or more plausible constructions. This lower threshold for ambiguity during prosecution allows examiners to identify unclear claims proactively. Similarly, In re Packard reinforced the USPTO’s authority to reject claims when applicants fail to resolve ambiguities identified in rejections. Together, these standards emphasize the applicant’s responsibility to ensure claims are clear before a patent is granted, preventing vague claims from entering the patent system.

In contrast, post-grant reviews and litigation apply the Nautilus standard, which is less strict than the USPTO’s prosecution standard. Under Nautilus, claims are invalid for indefiniteness only if they fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention. This more lenient standard respects the presumption of validity of issued patents, allowing some interpretive leeway. The stricter prosecution standard ensures clarity upfront, improving the quality of issued patents, while the Nautilus standard balances enforcement of patent rights with the practical challenges of drafting claims. Together, these standards maintain a fair and effective patent system by addressing indefiniteness at both the examination and enforcement stages.

December 17, 2024 - LKQ Relaxes Standard for Primary References - Design Elements in Three-Dimensional Article Cannot be Claimed in Two Dimensions under In re Maatita

LKQ Relaxed Standard for Primary References - App. No. 29/791,890 - Display Screen or a Portion Thereof with a Graphical User Interface – December 17, 2024

The examiner rejected the claim as obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103. The examiner cited the “Drag & Drop” design (a graphical interface featuring overlapping rectangles), in view of U.S. Design Patents D941,874 (Clediere) and D790,770 (Zhu), as references. While “Drag & Drop” exhibited overlapping rectangles with rounded corners, Clediere demonstrated reduced overlapping areas, and Zhu presented outlined rectangles. The examiner argued that combining these features would be an obvious modification, achievable by a designer of ordinary skill in the art, thereby rendering the claimed design unpatentable. This reasoning was supported by legal precedents, including In re Rosen, under which the “Drag & Drop” design served as a primary reference.

The applicant contested this rejection first by raising the new LKQ standard for obviousness. The examiner responded that “any rejection based upon Rosen/Durling is still effective under LKQ as LKQ merely relaxed the standards for primary references, rather than strengthened them. No rejection has been rendered moot by LKQ and therefore a response on the merits as much as possible should still be made.”

The applicant then responded by emphasizing the unique and distinctive features of the claimed design. The applicant argued that “Drag & Drop” depicted overlapping rectangles in different regions and proportions, and incorporating features from Clediere or Zhu would require hindsight and inventive effort beyond what an ordinary designer would undertake. After the examiner maintained the obviousness rejection, the applicant amended the drawings to add design features that rendered the design non-obvious.

Design Elements in Three-Dimensional Article Cannot be Claimed in Two Dimensions under In re Maatita – App. No. 29/814,057 – Tee Fitting – December 17, 2024

The examiner rejected the claim for indefiniteness under 35 U.S.C. § 112 because the depth and spatial relationships of the two inner circles in Figure 5 were unclear. Applicant argued that Figure 5 of the design drawings for a three-dimensional tee fitting met the definiteness and enablement requirements under § 112, citing In re Maatita as precedent. In that case, the Federal Circuit held that a design could be adequately disclosed using two-dimensional planar views if an ordinary observer could understand the design’s scope for infringement purposes. The Applicant contended that their provided figures, including Figure 5, disclosed the ornamental design sufficiently, allowing a designer of ordinary skill to grasp the claimed invention without ambiguity.

The examiner ejected this argument and distinguished Maatita from the current application. The examiner argued that while Maatita involved the relatively flat design of a shoe sole, the tee fitting was fully three-dimensional and required a more definitive description. The examiner claimed that the innermost circular elements in the tee fitting’s design were not clearly depicted in the figures, leading to an indefinite and non-enabling claim under § 112. This lack of clarity made the design incapable of being fully understood by someone skilled in the art.

To overcome the rejection, the Applicant amended the application by converting the disputed circular elements in Figure 5 to broken lines, indicating that these elements were not part of the claimed design. The applicant also submitted a substitute specification clarifying that the broken lines depicted unclaimed portions of the article. These changes ensured compliance with § 112(a) and (b) and led to the approval of the claim.

Comment: Applicants continue to argue that the reasoning in In re Maatita can be used to support the definiteness and enablement of certain design elements illustrated in two-dimensions in an article illustrated in three dimensions. Most of these efforts have failed at the USPTO and PTAB, although there have been exceptions (see, e.g., Ex Parte Chioccioni, Appeal 2018-007742, App. No. 29/430,805 (PTAB March 24, 2020) (Ice Cream Product). A good explanation for why the argument typically fails is contained in PTAB Decision Ex Parte Butcher, Appeal 2020-005018, App. No. 29/608,417, (PTAB April 2, 2021). In Butcher, the claimed design was a Transfer Case Gear Housing shown in sixteen drawing figures (two embodiments). A representative drawing is Fig. 2, which is a perspective view:

The examiner rejected the claim under 35 U.S.C. § 112 because the depth and spatial relationships of some of the design features were unclear. For example, the examiner argued that area marked by dark grey area A in the Figure 4 below left was unclear in the corresponding area in the Figure 4 below right.

The applicant/appellant argued that surface A is capable of being understood from the two-dimensional planar view perspective, and like in Maatita, the applicant’s decision not to disclose all possible depth choice of surface A does not preclude an ordinary observer from understanding the claimed design. Applicant/appellant argued further that “[t]he fact that the item has three-dimensional aspects does not preclude the full disclosure of the ornamental design using a two-dimensional view.”

The PTAB was not persuaded by appellant’s argument. The Board stated Appellant’s position “devolves to an argument that Maatita permits an applicant to claim a design partly in its three-dimensional appearance, and partly in a two-dimensional appearance.” No. 2020-005018, page No. 8 (PTAB April 2, 2021). The Board responded to the argument as follows:

“We do not read Maatita as approving of such a practice, nor as indicating in any way that using such an approach will not give rise to issues of indefiniteness and non-enablement. Maatita indicates that, where an appearance of a nominally three-dimensional article is presented in a single figure that is a two dimensional plan view, and the appearance of that article is capable of being understood from that view, the uncertainty of relative heights and depths of features appearing thereon does not, in and of itself, render a claim indefinite or non-enabled. Maatita expressly contrasts the shoe sole at issue there with an entire shoe and a teapot, stating that the latter two are not capable of being adequately disclosed with a single, plan- or planar view drawing. Maatita, 900 F.3d at 1376. We read this as the Maatita decision itself informing that the holding there does not apply to an entire article of manufacture, such as the transfer case gear housing of the present design, whose claim scope cannot be adequately ascertained without all aspects of the design being understood in three dimensions. Appellant’s transfer case gear housing is unlike the Maatita shoe sole in this respect, contrary to Appellant’s assertion. Instead, the housing is plainly akin to an article such as an entire shoe and a teapot, such that the overall appearance of the article cannot be adequately disclosed where portions of the overall three-dimensional appearance are illustrated in only two dimensions, with only single, plan- or planar views of those portions, leaving the entirety of the appearances of those portions to speculation.”

Id. at 8-9.

December 10, 2024 - Obviousness Test Requires Identification of Ordinary Observer and Consideration of all Views

Obviousness Test Requires Proper Identification of Ordinary Observer and Consideration of all Views - App. No. 29/858,880 - Medical Injection Device - December 10, 2024

The examiner rejected the claim under 35 U.S.C. § 103 alleging that the medical injection device design was unpatentable based on its similarity to two prior references: Fritz and Kern. The examiner argued that the differences between the claimed design and the prior art, such as the removal of circular elements from the device’s end, are minor and represent routine modifications that would be obvious to a designer of ordinary skill.

The applicant responded by emphasizing the need to properly apply the “ordinary observer test,” which evaluates the overall visual impression of a design from all perspectives, rather than a single view, and which correctly identifies the appropriate ordinary observer. The applicant explained that medical injection devices are typically observed by both retail consumers and medical professionals, making their unique perspectives crucial. Differences in the claimed design, such as centered labeling, margin patterns featuring circles with decreasing radiuses, and a larger expiration label, create a distinct visual impression that would be noticeable to these ordinary observers. The applicant argued that the examiner’s focus on limited views of the design, fails to account for these significant distinctions.

The applicant further argued that the cited prior art does not address or remedy the key differences. Fritz does not account for the unique features of the claimed design, and Kern does not cure these deficiencies. The applicant argued that these differences, while they may appear minor, collectively have a substantial impact on the overall visual impression of the design. The applicant requested the withdrawal of the rejection, and the examiner found the arguments persuasive and withdrew the obviousness rejection.

December 3, 2024 - LKQ obviousness analysis

New LKQ Obviousness Analysis - App. No. 29/911,351 - Attachment for Massage Device - December 3, 2024

The examiner rejected the design claim for a massage device attachment (Application No. 29/911,351) under § 103, citing it as obvious based on a combination of EU Patent No. 006629317-0005 (“Therabody”) and Chinese Patent No. 306055743 (“Zheng”). The rejection relied on perceived similarities between the “Therabody” reference and the claimed design, along with proposed modifications incorporating elements from “Zheng.” In response, the applicant argued that the rejection did not adhere to the updated obviousness framework established in LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Tech Operations LLC. (2024), which requires a four-factor analysis to determine obviousness. The applicant emphasized significant differences in the claimed design’s proportions, tapering, and cylindrical transitions, arguing that these distinctions created a substantially different visual impression compared to the prior art.

Ultimately, the examiner withdrew the rejection, agreeing that the proposed combination of references failed to achieve the claimed design’s appearance. This case reinforces key principles under the LKQ framework: the requirement that the proposed combination must result in the claimed design and the need to consider designs as a whole rather than focusing on individual features. The applicant demonstrated that the “Zheng” reference did not suggest the proportions of the claimed design and highlighted how the overall appearance of the claimed design — stout and continuous — differed from the thin, segmented profile of the prior art. This outcome underscores the importance of detailed arguments and comparing the designs as a whole when addressing design obviousness challenges.

November 26, 2024 - Complete Removal of Indefinite Line Results in 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) Written Description Rejection

Complete Removal of Indefinite Line Results in 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) Written Description Rejection – App. No. 29/838,497 – Neck Massage Device – November 26, 2024

The examiner issued an indefiniteness rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) and (b) because the appearance of the recessed circular area in Figs. 2 and 7 could not be determined. In particular, due to the lack of line shading or a view that clarifies its appearance, it could not be determined if the circular area is a flat surface, or a recessed surface of indeterminable three-dimensional configuration. The circular areas are shaded in gray and pointed out by the arrows in the image below of Figs. 2 and 7.

To overcome the rejection, the applicant converted some of the indeterminate solid lines to broken lines as follows:

The examiner then issued a Final Rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) because the design of the circular feature in figure 2 was not originally described. Specifically, the object line shown below in original Figure 2 is not shown in Replacement Figure 2:

The applicant then submitted a replacement sheet for Figure 2 showing the original object lines all being converted to broken lines as follows:

The examiner then withdrew the written description rejection.

Comment: Although it seems counterintuitive, complete removal of a design feature can result in a new matter rejection. If design features are considered indefinite and the option chosen to overcome the rejection is conversion to broken lines, then all the design features considered indefinite must be converted to broken lines rather than being removed.