USD1,055,187 - Issue Date: December 24, 2024

Key Point: The analysis for obviousness-type double patenting is similar but not identical to an obviousness analysis under 35 U.S.C. § 103. Three differences are that obviousness-type double patenting (1) compares claimed subject matter to claims in an earlier patent or patent application rather than to the prior art, (2) does not require inquiry into a motivation to modify the prior art, and (3) does not require inquiry into objective criteria suggesting non-obviousness. Applicants facing an obviousness-type double patenting rejection should consider focusing on visual distinctiveness and highlighting how the claimed design is unique rather than pointing out lack of motivation to modify the earlier design.

Other Points: Functional Considerations and Crowded Field Effect

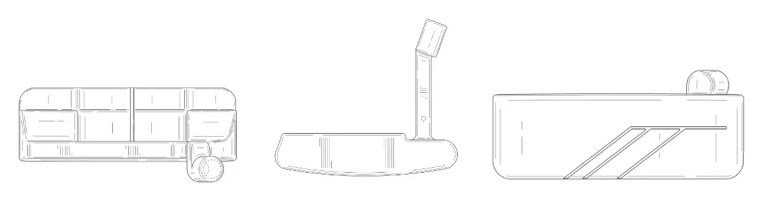

Summary: The USPTO issued a rejection for obviousness-type double patenting in design application 29/866,647, citing similarities to U.S. Patents D930,096, D967,914, and D979,680. The examiner argued that minor differences, such as variations in the striking surface shape, hosel (part of the putter that connects the club head to the shaft), and bottom patterns, were insufficient to render the claimed design patentably distinct. This rejection emphasized the perceived overlap in ornamental features between the designs.

In response, the applicant presented several counterarguments. First, the applicant argued the examiner had not set forth a rationale showing how an ordinary designer would be motivated to modify the earlier designs to create the claimed design, citing LKQ Corp. and KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc. Second, the applicant highlighted several significant ornamental differences in the claimed design and the prior designs, such as body proportions, hosel connections, and surface patterns. Third, the applicant emphasized the crowded nature of the golf putter design field, which would lead a designer of ordinary skill to notice even minor ornamental differences. Finally, the applicant pointed out functional elements that accentuated the ornamental distinctions. These arguments and supporting evidence led the examiner to withdraw the rejection.

Comments:

Differences between Analysis. Obviousness-type double patenting analysis differs from 35 U.S.C. § 103 analysis in three primary ways. First, it involves comparing a claim to another claim in an earlier patent or patent application – rather than to the prior art. Second, it excludes the consideration of objective non-obviousness criteria such as commercial success, copying, and industry praise. Third, unlike section 103 obviousness, double patenting analysis does not require a motivation to modify the earlier design. Therefore, the applicant’s argument above that a rationale was not presented for how an ordinary designer would be motivated to modify the earlier designs to create the claimed design arguably was more suited to a section 103 obviousness analysis. Applicants facing an obviousness-type double patenting rejection should consider focusing on visual distinctiveness and highlighting how the claimed design is unique rather than pointing out lack of motivation to modify the earlier design.

Functional Considerations: The applicant used functional considerations to bolster the argument that an obviousness-type double patenting rejection was not appropriate. Although design patents primarily are concerned with ornamental appearance and not functionality, functional considerations still can be relevant in an obviousness analysis. Here the applicant argued that the different hosel profiles “impart different aesthetics and functionalities” and “affect how the putter moves during a stroke,” App. No. 29866647, page No. 13, December 24, 2024, which further emphasized the distinctions to a designer of ordinary skill in the art of golf putter designs.

Crowded Field Effect: Finally, the applicant stressed that the crowded nature of golf putter design would lead a designer of ordinary skill to notice even minor distinctions in the designs. This is known as the crowded field effect in design patent law, and it exists in both obviousness and infringement analysis. The underlying idea is that in a crowded field, perceptual sensitivity is heightened, and even subtle differences are more visually impactful. For example, in the infringement context, the analysis requires determining whether an ordinary observer, familiar with prior art, would perceive a claimed design as substantially the same as an accused design. In a crowded field, the ordinary observer is already sensitized to the nuances of the field, making them more likely to notice and appreciate minor differences. The same crowded field effect occurs to the ordinary designer, who is charged with familiarity of all relevant prior art in the particular field. Note that in an obviousness-type double patenting analysis, although the claim is not being compared against the prior art, the state of the prior art (crowded vs. uncrowded) affects the perceptive abilities of the hypothetical designer of ordinary skill who is comparing one claim against another prior claim.